An Overview of a Foraminal Collapse in the Lumbar Spine

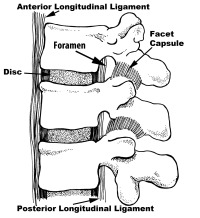

The foramen is the exit hole for the spinal nerve. This is the location where the nerve departs from inside the spinal canal into the pelvis and legs. Foraminal stenosis (stenosis means narrowing) occurs when this nerve hole narrows enough that the spinal nerve becomes pinched. Disc degeneration and bone spur formation are generally the origins of foraminal stenosis. Foraminal collapse in the lumbar spine occurs when the foramen becomes severely narrowed not only from foraminal stenosis but also due to an additional tilt of the vertebra above.

The foramen in the lumbar spine has four sides. These sides consist of the disc and endplates of the vertebra in front, the pedicles of each vertebra that make up the top and bottom walls and finally the facets, which make up the back wall.

The pedicles above and below the nerve can converge closer together when the disc narrows. This can squeeze the nerve root. The disc, endplates and facets (the front and back walls of the foramen) can grow bone spurs and also compress the nerve. A disc herniation can fill the foramen and also cause stenosis. A tilt (collapse) of the vertebra above can severely narrow the foramen.

Foraminal Collapse Symptoms

Foraminal collapse symptoms generate leg pain with standing and walking. Bending and sitting will reduce pain. Leaning over a counter will also relieve the pain. Pain is typically unilateral (only on one side). Pain in both buttocks or legs with standing typically is not a sign of foraminal stenosis but central spinal stenosis – a different type of disorder that is described on this website.

The occurrence of positional pain has to do with the biomechanics of the foramen. The vertebral foramen changes in volume with different positions. During flexion (bending forward), the foramen opens up. With extension (bending backwards), the foramen narrows. Lateral bending to the side of the narrowed foramen will close it down even further and leaning away from the compressed nerve opens up the foramen and relieves pain.

This is why patients with foraminal stenosis and especially with foraminal collapse will tend to lean forward and away from the pain when standing. These individuals will adopt a list (a lean) or a flexed (bent forward) position when they stand. This positioning might also be continued while sitting in severe cases.

Patients with mild foraminal stenosis will commonly bend forward when they walk to keep the foramen open and avoid symptoms. This positioning might not be easily noticeable. Patients with significant foraminal stenosis will also lean away from the pain as well as bend further forward to try and relieve symptoms when they stand and walk. Interestingly, many of these patients have not looked in a mirror. They are surprised when they discover during the physical examination that they have adopted this antalgic positioning without their knowledge.

If the stenosis is more significant, there will be a point with standing and walking that the pain will be too significant to bare and the patient will need to sit down, crouch forward or lie down to relieve the pain. If the stenosis is very severe, once the pain occurs, it might take hours for the pain to be reduced. The pain might not abate at all, even with determined flexion and lean. Finally, with extreme compression, motor weakness can develop.

The pain will generally occur in specific regions in the leg depending upon the nerve root involved. For example, the L5 root can radiate pain all the way down the leg to the inside of the foot. The L4 root can radiate pain down the back of the leg across the knee into the front of the calf. The L3 root will radiate pain into the front of the thigh and the knee. The L2 root can radiate into the groin and front of the thigh and the L1 root can radiate into the groin. All of these roots are individually capable of radiating pain into the sacroiliac joint and buttocks. These pain patterns are not absolute as there are variations from individual to individual.

Nerve root compression does not have to radiate all the way to the termination of the root. That is, with moderate but not severe compression, pain generated from the L5 root might only radiate into the buttocks and the back of the thigh but not into the shin or foot. However, the longer the individual stands or walks with pain, the further the pain will radiate down the leg,

Many times, the presence of foraminal collapse is asymptomatic (no pain present) until a specific activity (a jump, twist, lift or impact) or an awkwardly held position occurs. Leg pain then seems to originate out of nowhere and does not relent. What has occurred is that the nerve had become pinched and due to this compression then swells. Unfortunately, this swelling enlarges the root’s diameter and makes the root less able to “fit” into the already narrowed foramen. The root is then more easily compressed with standing and walking.

Foraminal Collapse Pathology

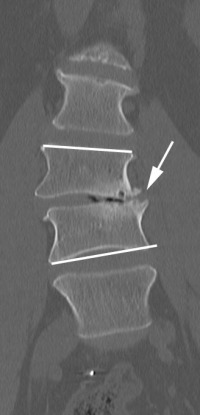

The normal height of the disc makes up at least half of the height of the foramen. With severe disc degeneration, the height of the disc is lost. This narrows the foramen substantially. Bone spurs in the face of disc degeneration also normally grow in the front where the adjacent vertebrae come into contact. These spurs grow into the foramen, which further narrows this exit hole.

When the disc degenerates, the facets in the rear of the foramen imbricate (compress together). This increased compression wears out these joints quickly. Wear leads to further bone spur formation from the rear of the foramen. Ganglion or synovial cysts can also grow from these degenerative joints further narrowing this exit hole.

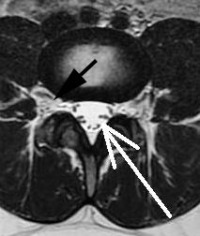

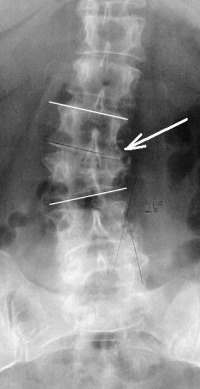

With “normal” foraminal stenosis (no angular collapse) when the disc degenerates, the disc collapse is symmetrical. That is, the disc loses height equally on each side and the endplates of the vertebra stay parallel to each other. Foraminal collapse differs in that the disc degeneration occurs only on one side and the vertebra takes on a significant tilt. This tilt causes the foramen on the collapsed side to become extremely narrowed. The additional pressure focused only on this one side wears the facets out even faster.

Foraminal collapse can be associated with a degenerative scoliosis but typically will be independent of a scoliosis.

In the face of this abnormal pressure due to the angulation or tilt, bone spurs form on the collapsed side. These spurs create a buttress to prevent further angulation and collapse. The dilemma for surgical decompression is that this bony buttress has to be removed to free the nerve but the bone spur removal allows for further instability and further collapse.

The diameter of the normal nerve is typically large enough to fill half of the normal foramen. By understanding the pathology above, you can appreciate that foraminal stenosis reduces by at least half, the volume of the normal foramen. Foraminal collapse reduces the volume of the foramen by at least 75% and many times even more.

Are you suffering from symptoms of foraminal collapse in the lumbar spine?

Would you like to consult with Dr. Corenman about your condition?

You can set up a long distance consultation to discuss your

current X-rays and/or MRIs for a clinical case review.

(Please keep reading below for more information on this condition.)

Diagnosis of Foraminal Collapse

Diagnosis of this lumbar spine condition is relatively easy. Patients with standing/walking pain in only one leg that have an angular collapse of 5 degrees or greater on their standing X-rays and MRI evidence of foraminal stenosis on the painful side most likely have foraminal collapse.

A selective nerve root block (SNRB) that yields temporary relief of the pain generally confirms the diagnosis (see pain diary on the website). Diagnosis using a SNRB can occasionally be tricky due to severe narrowing. Some individuals have such extreme narrowing that an SNRB will not yield temporary relief, as the numbing medication cannot reach the entire trapped nerve root. In cases like this, a SNRB and ESI (epidural steroid injection) at the same time might have to be considered to give a complete diagnostic picture.

Surgery For Foraminal Collapse

Surgery for foraminal collapse assumes that prior treatment (physical therapy, chiropractic, injections, medications and activity restrictions) were not successful to manage this disorder.

The pressure of the vertebral column above the tilted and collapsed vertebra produces forces that lead to further angular collapse. What prevents continued collapse is the buttress bone spur formation on the collapsed side. Unfortunately, this bony buttress is also one of the major causes of the narrowing of the foramen.

A simple foraminotomy (a “roto-rooter job”) is much more likely to fail in the presence of foraminal collapse. First, the foramen is more narrowed in foraminal collapse secondary to the bone spur buttress and tilt. The second and more important reason is that a significant amount of bone is required to be removed to free up the nerve root. This same bone has formed to mechanically stabilize the progressive tilt of the vertebra. Removing this bone to decompress the nerve root will allow further collapse of the vertebra and renewed compression of the nerve root after surgery.

Since the recurrence rate of nerve compression from foraminotomy is very high in the presence of foraminal collapse, the appropriate surgical procedure for foraminal collapse is a TLIF fusion of this level. This procedure allows a thorough decompression of the nerve root by completely removing the offending facets (the back wall of the foramen). In addition, the nerve can be visualized from its origin to its exit and any anterior bone spurs or herniations that have compressed the nerve from the front can be removed as well.

Finally, the side of the collapsed disc can be re-leveled to correct any deformity of the spine with a TLIF fusion. This will reduce the slip angle (tilt) of the vertebra above and reduce the tendency of the vertebra above to slip to the side (a lateral listhesis) This leveling is performed by placing a “cage” or spacer into the collapsed side of the disc space to “re-level” the disc.

In general, success rate of a TLIF fusion for relief of leg pain from foraminal collapse should be greater than or equal to 90%.

To learn more about foraminal collapse in the lumbar spine, please contact the office of Dr. Donald Corenman, back doctor and spine specialist in the Vail, Aspen, Denver and Grand Junction, Colorado area.

Related Content

- When to Have Lower Back Surgery

- Causes of Lower Back Pain

- Normal Spinal Alignment

- Lumbar Spinal Alignment

- How to Describe Your History and Symptoms of Lower Back and Leg Pain

- Best Questions to Ask When Interviewing a Spine Surgeon or Neurosurgeon

- Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

- Isolated Disc Resorption-Lumbar Spine (IDR)

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (Central Stenosis)