Anatomy of the Neck

The neck or cervical spine is the top part of the spine between the head and shoulders. The cervical spine has seven vertebra of which the bottom five are designed similarly and the top 2 are very different.

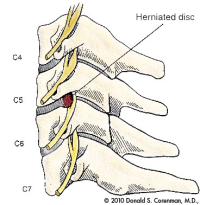

Most of the problems or conditions from the neck come from the bottom 5 vertebra (cervical vertebra 3 through cervical vertebra 7 or more commonly called C3-7). Each vertebra has a large body in front separated by a disc and two medium sized joints or facets in back. In the center, there is a large (normally) spinal canal which houses the spinal cord.

Nerves in the Neck

Two nerve roots (one on each side) sprout from the cord at each level and exit between the two adjacent vertebra through a hole on the side of the spine called the foramen. For example, the right C6 nerve root exits the spinal canal between the right C5 and C6 vertebra. The hole the nerve exits out of is made up of four walls which is important as will become apparent later as we discuss problems with the neck. These are the disc wall and uncovertebral joint in front, the pedicle above as the roof, and pedicle below as the floor and the back wall, which is the facet.

These nerve roots deliver their messages to and from the back and sides of the head and down the shoulders and arms to the hands. The spinal cord of course sends and receives messages from the entire lower body and is really an extension of the brain.

Spinal Discs in the Neck

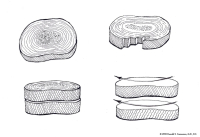

The disc is the shock absorber in the front of the spine wedged between two vertebra. It is designed like a jelly filled donut. The nucleus (jelly) inside is under high pressure and the outer part of the donut is the annulus- essentially 20-30 rings of collagen just like plies of a tire that hold in the jelly.

The discs are named for the vertebra they are sandwiched in-between. For example, the disc wedged between the vertebra C5 and C6 is the C5-6 disc. There is no disc between C1 and C2 nor between the occiput (head) and C1. Every other level has a disc associated down to the pelvis.

The paired joints in back (called the facets) are real joints similar to knee or hip joints. These facets are made up of 2 bony surfaces covered with cartilage (similar to a Teflon substance) and surrounded by a capsule, which is a heavy burlap sack-like material. This capsule keeps the lubricating fluid in (synovial fluid) and provides strength to hold the joint together.

The uncovertebral joint is an interesting structure that develops slowly in all humans after birth and actually is the only joint in the body that is not present during birth. It is located on the very outside of the sides of the disc between 2 vertebra and develops bilaterally (on both sides). It becomes important as a troublemaker with aging as it can develop bone spurs which can narrow the exit hole for the nerve.

Vertebra in the Neck

The first two vertebra are very important as they are responsible for 50% of the motions of bending forward and backwards and turning the head side to side. Their design is very different from the bottom five. During in-utero development, the first vertebra called C1 or the atlas literally donates its body to C2 or the axis. This donation allows C2 to have a peg called the odontoid that the first vertebra rotates around. There is a very thick and important ligament called the transverse ligament that holds C2 to C1 and keeps the two vertebra stable.

Related Links

- Normal Spinal Alignment

- Anatomy of Thoracic Spine

- Anatomy of Lumbar Spine

- When to Have Lower Back Surgery

- When to Have Neck Surgery

- How to Describe Your History and Symptoms of Neck, Shoulder and Arm Pain

- How to Describe Your History and Symptoms of Lower Back and Leg Pain

- Anatomy and Motion of the Cervical Spine

(Click to Enlarge Image) This illustration is a side view of the cervical spine (neck). Here you can see the vertebral bodies with the discs in the front of the spine and the facets in the rear. The nerve roots exit through the sides of the spine.

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is a MRI side (sagittal) view of the cervical spine. It demonstrates good disc spaces, a normal curve (lordosis), plenty of room for the spinal cord and good alignment of the facets.

(Click to Enlarge Image) This illustration demonstrates the anatomy of the annulus. The annulus is made up of about 30 rings of collagen- just like plies of a tire. You can see that the orientation of the fibers alternate with each layer. This makes for a strong and redundant disc wall when the spine is in neutral but with twisting (rotation), half of the fibers undergo tension and the other half become relaxed. The picture on the lower right demonstrates this phenomenon. Rotation of the spine therefore weakens the disc wall and it becomes more susceptible to tearing. Moral of the story- don’t twist when you lift!