Symptoms of a Herniated Disc

The varying stages associated with a lumbar spine herniated disc will cause moderate discomfort to intense pain in the lower back, legs or buttocks depending on the stage of the herniation. The most common symptoms are a dull, nagging pain in the lower back region, which progressively becomes more severe resulting in a sharp lower back pain.

There are different distinct symptoms depending on exactly where the injury is.

- L4, L5 and S1 nerve: This nerve, a combination of L4, L5 and S1 in the spine, travels down behind the back of the pelvis before it descends down through the leg to “attach” to the foot. When the leg is raised or the patient bends forward, the nerve is stretched over the pulley of the pelvis and pulled into the disc herniation. Pain is usually felt in the buttocks and leg. Patients may feel better with standing and will most likely feel worse with sitting. If the disc herniation is in the typical posterolateral position, sitting will aggravate sacroiliac and leg pain. Standing or lying down gives some relief. Patients also won’t like to bend over to tie their shoes. This holds true if the herniation is at the lower two discs. The reason is that the sciatic nerve is involved.

- L2, L3 and L4 nerves: If the herniation is at the disc level L3-4, the symptoms will change. The femoral nerve originates from the roots L2, L3 and L4. In addition, the sciatic nerve is stretched by raising the leg. This motion however, relaxes the femoral nerve. The opposite motion causes the femoral nerve to be stretched. Leg extension (bending the leg behind the body at the hip) pulls on this nerve. The reason is that this nerve travels down the front of the pelvis and “attaches” to the front of the thigh and leg. Any backward movement of the leg stretches the nerve over the “pulley” in front of the pelvis, and pulls it into the disc herniation.

Weakness may be associated with a herniated disc and depends upon what nerve is affected. Unlike the neck, weakness in the leg is more serious. The nerves that go to the leg are much more sensitive than other nerves and do not recover as well or as completely.

Treatment of a Herniated Disc

Non-Surgical

In 70% of cases, surgery will not be required to remove a herniated disc of the lumbar spine. Medications, cold and hot therapies, epidural injections, physical therapy and rest can often relieve the condition. If the condition persists, then surgery may be recommended. Weakness is one sign that surgery is warranted.

Surgical

The most common surgery performed to treat a herniated disc in the lumbar spine is a microdiscectomy. The protruding part of the disc is removed so that nerve root pressure can be relieved. Most times, this procedure can be performed microscopically which will use a smaller incision and lead to a faster recovery. The success rate is about 90-95% for relief of pain but weakness can take much longer to recover from and there are occasions that permanent weakness could occur. This is the reason that herniations with weakness are taken to surgery more quickly and frequently than ones with pain but no weakness. The chance of recurring herniations is present as the hole in the disc wall does not heal fully (no blood supply).

For more information on herniated discs associated with the lumbar spine, please contact the office of Dr. Donald Corenman, back doctor and spine specialist in the Vail, Aspen, Denver and Grand Junction, Colorado area.

Related Content

- When to Have Lower Back Surgery

- Causes of Lower Back Pain

- Normal Spinal Alignment

- Lumbar Spine Anatomy

- How to Describe Your History and Symptoms of Lower Back and Leg Pain

- Best Questions to Ask When Interviewing a Spine Surgeon or Neurosurgeon

- Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

- Isolated Disc Resorption-Lumbar Spine (IDR)

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (Central Stenosis)

Herniated Disc in the Lumbar Spine Overview

If you have ever experienced lower back pain, then you are certainly not alone. The lumbar spine (which is the technical term for the lower back) represents an area where many injuries and disorders can occur. One of the most common problems we treat in our practice are herniated discs that are associated with the lower back. Herniated discs in the lumbar spine can cause a great deal of lower back pain and leg pain.

The Lumbar (Lower) Spine

Between each vertebra in the spine is a disc. These discs are the main stabilizers in the spine. They function like restricting shock absorbers. Each disc is in place to absorb impact and still allow motion of the spine, but it has to restrict this motion to prevent damage to the spine. This is a great deal to ask of a tissue and is the reason why the lower spine is so susceptible to injury.

Each disc in the lower back surround an element known as the nucleus pulposus which is a gel-like substance within the spine. The easiest way to describe these discs is to compare them to a jelly-filled donut. The inside jelly (nucleus) is made of sugar attached to protein and acts like a giant sponge. This material pulls in water from the body of the vertebra to create a high-pressure interior mass. The outside of this donut (annulus) is made up of about sixty rings of collagen. These rings are quite tough. The endplates of the vertebra separate the bone from the disc. These endplates are made of cartilage – the same cartilage that lines the hip and knee joints. This material creates a barrier to nutrients and oxygen flowing into and out of the disc.

Problems Associated with the Lumbar Spine

After the age of eight the blood flow to these discs naturally begins to disappear. This leaves the interior of the disc in the adult with no blood supply. Therefore, the only fluids that can be exchanged are under pressure. This effect is evident in our height differences throughout a typical day. When we get up in the morning, we are actually one-half inch taller than we are in the evening. The pressure inside the disc with prolonged standing squeezes water out, making the disc less thick. Therefore, the spine has less height at the end of the day. Motion of the disc exchanges fluids similarly to squeezing a sponge under water. Fluid is forced out and then reabsorbs. This barrier significantly restricts nutrient and waste exchange.

Without oxygen, the cells inside the disc that manufacture the shock-absorbing protein that make up the jelly become senile. Without the production of these proteins, the pressure in the disc drops. When the pressure drops, the walls of the disc (the annulus) take more of the strain and are at more risk to tear. Therefore, a degenerative disc is much less resistant to abnormal movements and these motions can create injury.

Another problem with the disc is the type of collagen that makes up the outside of the donut. Not all collagen is created equal. Some types of collagen can be bent and stretched continuously and they will continue to function as though they were new, while other types of collagen are somewhat brittle, like coat hangers. You can bend them only a limited amount of times before they fail. The genetics of the discs go a long way in predetermining the health of your back. This gives you a good reason to shift responsibility for your back pain to your parents.

Herniated Discs in the Lumbar Spine

You can see that the disc is mechanically and biologically at risk. The disc is the largest structure in the body that has no blood supply. Without a blood supply, the disc can’t heal after an injury. All injuries to the disc therefore are cumulative. To say it another way, any injury to the disc is, essentially, a permanent injury. A tear of the collagen in the donut won’t repair itself. If you were born with brittle or weak collagen, there is a greater risk of injury to the disc.

What happens if you develop an annular tear? If one of these discs, or outer bands breaks or cracks open, the gel-like substance inside can spill and leak out causing a herniated disc. This leakage ultimately puts pressure on nearby nerve roots and on the spinal cord itself. In addition, the substance that makes up the nucleus also contains elements that can cause inflammation within the nerve, which can lead to a dull aching pain in the lower back once released into the spinal chord.

When there is a tear of the outer disc wall, a very weak supply of blood is available to assist in the healing process. Tears will attempt to heal, but the scar tissue laid down is not nearly as strong as the collagen fibers it attempts to replace. In addition, blood vessels that grow into the torn fibers of the disc carry new pain fibers in with them. This is another cause of pain for the disc.

This is ultimately an extension of degenerative disc disease. The tear in the disc (which itself causes back pain) can finally rip through and through and the jelly inside (nucleus) can be forced out just like squeezing a toothpaste tube with the cap off. The resultant herniation material pushes against the nerve root and leg pain ensues.

One of the more interesting scenarios associated with a herniated disc in the lumbar spine is that in some cases, the patient may have had low back pain for months to years. When the patient lifts or twists, a “pop” occurs in the lower back resulting in a complete through and through disc tear. Patients will have immediate relief of their ongoing back pain. This is because the scant remaining intact fibers of the disc were under significant tension. When these fibers rupture, the back pain disappears. This tear of the remaining fibers however allows the nucleus to herniate, which compresses the nerve root. Leg pain sometimes takes 1-2 days to occur after the herniation, so there is a short period of total relief

Stages of a Herniated Disc

There are several stages of a herniated disc in the lumbar spine. Over time, due to wear and tear of the spine and due to age, the discs will naturally weaken. During this stage, very minimal symptoms may be present such as periodic slight back pain. The next stage usually results in a prolapsed disc whereas the shape or form of the disc may have a bulge resulting from a slight impingement into the spinal canal. If the gel-like nucleus pulposus actually breaks through the outer later but remains inside the disc, an extrusion will occur. The final and most serious stage is a sequestered disc which will occur when the nucleus ruptures and breaks essentially spilling the substance into the spinal canal.

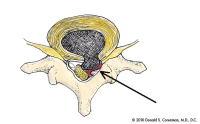

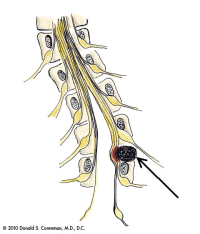

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is a diagram of a herniated disc of the lumbar spine. The cross-hatched area shows the jelly pushing through the tear in the back wall of the disc and the compression of the nerve root (arrow). Compare this side to the opposite side where the nerve is in its normal anatomic position.

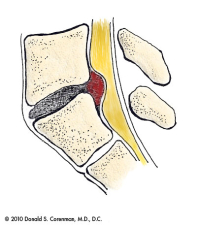

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is an illustration of a lumbar herniated disc seen from the side view.

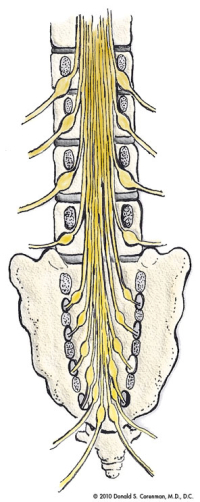

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is a cut-away front to back view of the lumbar spine which demonstrates how the nerves are distributed in the lower back. You can see which nerves are right next to the disc space and which nerves lie in the foramen (both places where the nerves can get trapped).

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is a picture of an antalgic scoliosis of the lumbar spine. The patient unconsciously leans away from the herniated disc (arrow) to take pressure off of the nerve root. Compare this with the normal diagram of the spine with nerve roots above.

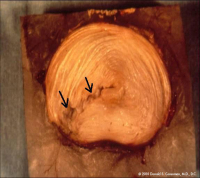

(Click to Enlarge Image) The first picture is looking down at an intact normal disc. (These pictures are of a lumbar spine disc but the cervical spine discs are almost exactly the same).The pink center is the nucleus (jelly in the donut) and the outer beige area is the annulus (donut of jelly donut fame). You can see the rings of collagen if you look carefully. Behind the disc lie the nerve roots seen in yellow. The facets in the back of the spine are seen in blue.

(Click to Enlarge Image) The second picture is of an annular tear in the back of the disc (arrow). The tear partially goes through the annulus. Note that the jelly pushes into the fibers of the annulus. The back wall of the annulus is full of pain receptors. This jelly is also neurotoxic so exposure of the pain nerves to this substance has an additional inflammation penalty.