An Overview of

A degenerative spondylolisthesis is a common condition of the lumbar spine that normally occurs more commonly in females than males but does occur in both groups. In a nutshell, what occurs is that the disc between the two vertebrae wears out and the facets in the back of the spine wear out and erode. The vertebra on top slides forward on the vertebra below. This condition can cause narrowing of the spinal canal (central spinal stenosis), narrowing of the hole the nerve exits from (foraminal stenosis) and painful abnormal movements of the vertebra with bending and twisting (instability).

The most common area for a degenerative spondylolisthesis is L4-L5. Most frequently, this disorder occurs in women but men are not immune to this condition. It is estimated that one in five women will develop this slip by the age of forty five.

Anatomy

The lumbar facets are the joints in the back of the vertebra that are paired and hook the rear of the top vertebra to the back of the vertebra below. With movement, they are important in causing the spine to track properly. The disk in front absorbs shock and dampens motion but it is the facets in back that are crucial in guiding the motion of the vertebra like railroad tracks guide a train.

When it comes to bearing weight, the disc in front carries almost 80% of the weight and the facets only 20%. This weight bearing distribution changes with forward and backward bending. Bending forward causes the disc to bear almost all the load and bending backwards causes the facets to bear almost 70% of the weight of the upper body.

The facets are real joints similar to a hip or knee joint. A joint is essentially a movable surface located where two bones join together. In this type of joint, called a diarthrodial joint, both joining bones have smooth caps of cartilage that covers the surfaces. These facet joints are held together with a strong flat sheet of collagen called a capsule that surrounds the joints. Lining this capsule is the synovium, a thin sheet of specialized cells that make the lubricant- synovial fluid- similar to WD 40 oil.

The joint surfaces are so perfectly matched and smooth that with the synovial fluid, there is a vacuum that holds the joints together. Breaking this vacuum causes a popping sound similar to removing a wet glass from a smooth counter. There is no danger in breaking this vacuum and it can feel quite good, as when a Chiropractor manipulates the spine.

Abnormal movement of the facets, as commonly seen with an associated degenerative disc can cause uneven wear of the cartilage and even cause some of the joint surface to sheer off. The smooth lining of these facets (the cartilage) has a very poor blood supply and cannot heal if injured. “Degenerative facet arthritis” or “degenerative facet disease” is the term used for the wearing down of the cartilage surfaces in the spine.

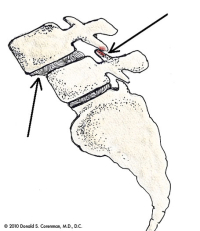

The facets mechanically are “door stops”. Looking carefully at a side view of a normal lumbar x-ray, the vertebra all line up perfectly. With degenerative changes of the disc, the height of the disc is lost. The vertebra involved will slide backwards on the one below (called a retrolysthesis) because they are shaped like a ramp facing backwards. However, in spite of a degenerative disc being present, if the facets have worn out and eroded away, the vertebra above will slide forward. This condition is called a degenerative spondylolisthesis. (If the facets break off, the condition is called isthmic spondylolisthesis. Please see the separate section on this condition elsewhere in this web site).

The forward slip of the upper vertebra on the lower one has ramifications for the diameter of the spinal canal. Since the canal is a series of concentric rings piled one on top of another, the forward slide of the upper vertebra will significantly narrow or pinch the canal. Because the canal, with or without this pinching will enlarge with forward bending and decrease in size with backward bending, you can imagine what happens to the canal that is already narrowed with backwards bending. Of course, backwards bending of the lower back is necessary for standing and walking. This narrowing of the canal will cause a condition called neurogenic claudication. See the symptom section below for a description of the symptoms involved.

The facets, when they become degenerative, develop bone spurs. If the bone spurs push medially (inside the spinal canal), then lateral recess stenosis occurs (crowding of the traversing nerve root). If the spurs form in front, foraminal stenosis results (crowding of the exiting nerve root). If the facet spurs tear the capsule, a ganglion cyst can form which can cause stenosis in either location. Please see these topics covered elsewhere in this web site.

(Click to Enlarge Image) This picture shows the anatomy of a degenerative spondylolisthesis. The arrow in the front of the spine (left side of the picture) points to the step-off or slip of one vertebra on the one below. The arrow in back points to the cause of the slip, the wear of the facet joint allowing the slip.

(Click to Enlarge Image) This is a CT of a damaged joint in the lumbar spine. The arrow points to the arthritic and subluxed (misaligned) joint.

Are you suffering from symptoms of degenerative spondylolisthesis.?

Would you like to consult with Dr. Corenman about your condition?

You can set up a long distance consultation to discuss your

current X-rays and/or MRIs for a clinical case review.

(Please keep reading below for more information on this condition.)

Symptoms of Spinal Stenosis

(please also see section Lumbar Spinal Stenosis)

Spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis can cause neurogenic claudication. Neurogenic claudication is a constellation of symptoms. The classic complaints are that the longer the individual stands or walks, the buttocks area becomes “achy and numb” and the legs become “heavy”. The more prolonged the walking, the more intense the symptoms become until they are intolerable. Pain or numbness will radiate further down the legs the longer one stands or walks. Finally, the affected individual has to sit down or bend forward, commonly crouching to relieve the pain. After a period of time, the symptoms resolve and walking can commence again. The cycle then repeats itself.

There is a subset of neurogenic claudication patients who have only lower back pain and no leg symptoms. This particular type of back pain is increased with standing and walking and relieved with bending forward. This is different from patients with degenerative disc disease who get some relief from bending backwards and are aggravated by bending forward. For reasons yet to be understood, the pain from neurogenic claudication is only localized and does not radiate down into the buttock and legs.

If lateral recess stenosis or foraminal stenosis occurs, the pain will be aggravated with the same activities as above but it will occur in only one leg as only one nerve is compressed.

If the patient has accompanying instability, symptoms of instability include lower back pain accompanied with an on-going unstable sensation within the region. Many patients find it difficult to rotate their mid-section. Muscle spasms are also a common occurrence for patients experiencing instability. A painful clunk can occur with motion and an unprepared patient who steps off a too high curb will get an electrical jolt to their back.

Patients with stenosis will unconsciously try to keep their back flat when they walk to keep the canal as open as possible. The only ways to do this are to rotate the pelvis posteriorly and to bend forward. Bending forward while walking wastes a tremendous amount of energy and quickly becomes exhausting. To compensate for this, many patients will keep their knees bent while walking. This maneuver is still very inefficient, but saves more energy than the alternative.

Treatment

Non-Surgical

Non-surgical treatments can manage the symptoms of lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. Non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory medication along with physical therapy and prescribed exercises typically work well. A core strengthening program and neutral spine program are important. Epidurals are a mainstay of treatment.

Surgical

There are surgical procedures that can help relieve the pressure on the nerves and therefore the symptoms of degenerative spondylolisthesis with lumbar central stenosis, lateral or foraminal stenosis or instability.

A decompressive laminotomy or laminectomy can be performed to create more space in the spinal canal for the nerves. This is done by removing a portion of the roof of the canal and any spurs that have grown into the canal from the degenerative facets. This is essentially a roto-rooter surgery to make more room for the nerves. Please see section on surgical options for this procedure.

If instability has occurred along with spinal stenosis (example is unstable degenerative spondylolisthesis) spinal fusion stabilization procedure may be required in addition to the decompression surgery. Please see section on surgical options for this procedure.

For more resources on degenerative spondylolisthesis, please contact the Vail, Aspen, Denver and Grand Junction, Colorado area office of spine surgeon and back specialist Dr. Donald Corenman.

Related Videos

Related Content

- When to Have Lower Back Surgery

- Causes of Lower Back Pain

- Normal Spinal Alignment

- How to Describe Your History and Symptoms of Lower Back and Leg Pain

- Best Questions to Ask When Interviewing a Spine Surgeon or Neurosurgeon

- Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

- Ganglion Cysts

- Isolated Disc Resorption-Lumbar Spine (IDR)

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (Central Stenosis)